Can you patent software? Former U.S. Patent and Trademark Office Director Andrew Iancu recently acknowledged that the law surrounding patentable subject matter has become too complicated. Although we deal with this issue nearly daily, the current state of the law makes it practically impossible to provide a clear and concise answer to anyone who asks us – “Is my invention patentable?”

Judge Plager of the Federal Circuit criticized the current patentable subject matter test in a July 2018 decision, Interval Licensing LLC v. AOL Inc. Simply put, right now, no one (not even Federal Circuit judges) knows how to answer this question, because the law is in flux. But how did we get here?

In the 1980 Supreme Court case, Diamond v. Chakrabarty, the Court opined that anything under the sun made by man is eligible for patenting. Unfortunately, it is not that simple, especially with respect to software and computer-related technologies. In 1981, the Supreme Court decided Diamond v. Diehr. In this case, the Court held that a computer-implemented process for curing rubber was patent eligible. Although there were rapid advances in technology, the Court would not take up patentable subject matter of a computer-implemented process again until 2014.

In 1998, the Federal Circuit decided State Street Bank, where the court found that an invention was eligible for patent protection if “it produces a useful, concrete and tangible result.” State Street Bank and Trust Company v. Signature Financial Group, Inc., 149 F.3d 1368 (Fed. Cir. 1998). After State Street, it was widely believed that business methods and software were patentable. This led to a great increase in the number of computer-implemented patents and patent applications. By 2011, software related patent applications represented nearly fifty percent of the patent applications in the United States.

In 2006, the Supreme Court decided a patent case related to whether an injunction should be granted when there is patent infringement. In a concurrence, Justice Kennedy noted that “In addition injunctive relief may have different consequences for the burgeoning number of patents over business methods, which were not of much economic and legal significance in earlier times. The potential vagueness and suspect validity of some of these patents may affect the calculus under the four-factor test.” This was seen as a red flag that changes may be coming.

Those changes eventually came in 2014, when the Supreme Court decided Alice v. CLS Bank, the first case associated with patent eligibility of computer-implemented inventions since 1981. In Alice, the Court found a computer-implemented invention related to facilitating financial transactions to be directed to something that had been done for a very long time without a computer. The Court indicated that implementing the financial transactions using a computer was simply an abstract idea and was not patentable subject matter.

The Court issued a two-part test that includes determining whether a patent claim is directed to an abstract idea and if so, whether the claim includes significantly more such that the claim amounts to significantly more than the abstract idea. Unfortunately, the Court did not explain what makes something abstract and did not explain what is “something more.”

In the aftermath of Alice, the USPTO withdrew notice of allowances for a large number of software and computer-implemented patent applications.

The Federal Circuit and federal district courts have been struggling with how to decide these issues since Alice. In the meantime, Alice has provided a sea change to the patent world, especially related to software. In some e-commerce related art units, the patent office has allowed nearly 0% of patent applications since Alice. Computer-implemented inventions have also suffered high rates of invalidation in district courts. In many cases, 12(b)(6) motions to dismiss are granted.

At the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), software and computer-implemented inventions have also suffered a similar fate. As of 2016, the PTAB had decided nearly 90% of challenged patents to be invalid.

In fact, things were so dire in 2016 that the Federal Circuit had to acknowledge in Enfish v. Microsoft that “we do not read Alice to broadly hold that all improvements in computer-related technology are inherently abstract.” A very high percentage of patentable subject matter cases decided by the Federal Circuit since Alice have held software and computer-implemented inventions to be invalid.

On April 19, 2018, the USPTO published a memorandum entitled “Changes in Examination Procedure Pertaining to Subject Matter Eligibility, Recent Subject Matter Eligibility Decision (Berkheimer v. HP, Inc.). In this case, Judges Lourie and Newman from the Federal Circuit encouraged Congress to clarify patent eligible subject matter. They explained that there is too much confusion caused by Alice. Former Chief Judge Paul Michel has also gone on the record to state that the U.S. patent system is in crisis mode. And Director Iancu understands that the pendulum may have swung too far. It appears that the Berkheimer case and the memo may have some major implications regarding Office policy and subject matter eligibility.

In early June 2018, the USPTO filed two motions to vacate and remand two different decisions of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) to reconsider the rejections of claims under 35 U.S.C. § 101 based on Berkheimer. This represents a direct shift and shows that the USPTO has begun to realize that Alice v. CLS Bank has greatly muddied the waters with respect to patentable subject matter, in ways that go far beyond what the Supreme Court intended.

This was further demonstrated by Director Iancu at the recent IPBC Global Conference in San Francisco. On June 11, 2018, then Director Iancu questioned whether Thomas Edison’s invention of the phonograph would meet the Alice test. He also questioned whether anyone in the room could explain, simply and clearly, what matter exactly qualifies as patent eligible in the United States.

Former Director Iancu was not the only one that was confused. On July 20, 2018, Judge Plager of the Federal Circuit provided an opinion, concurring in part and dissenting in part in Interval Licensing LLC v. AOL, Inc. Although the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s finding that the claims at issue were directed to patent ineligible subject matter, Judge Plager provided his take and noted that “[t]he law, as I shall explain, renders it near impossible to know with any certainty whether the invention is or is not patent eligible.” Judge Plager then dissented from “our court’s continued application of this incoherent body of doctrine” by explaining that with respect to determining whether a claim includes an abstract idea, “only the judges who have the final say in the matter can say with finality that they know it when they see it.”

Although Alice has changed things significantly, under Director Iancu the pendulum swung back in the direction of software and computer-implemented inventions. Judge Plager has invited Congress to solve the problems created by Alice but that has not yet happened.

On January 7, 2019, the USPTO published its 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance (2019 PEG) and five new additional subject matter eligibility examples related to abstract ideas. 2019 PEG will supersede previous guidance and the USPTO sought public comment on this guidance until March 8, 2019.

The 2019 PEG and the five additional examples and represent a significant change from the previous guidance and examples provided by the USPTO. The director of the USPTO, Andrei Iancu, acknowledged that “[t]he legal uncertainty surrounding Section 101 poses unique challenges for the USPTO, which must ensure that its more than 8500 patent examiners and administrative patent judges apply the Alice/Mayo test in a manner that produces reasonably consistent and predictable results across applications, art units and technology fields.” (2019 PEG, p. 3). Thus, the goal of 2019 PEG is to increase clarity and consistency in examination with respect to the Alice/Mayo subject matter eligibility test.

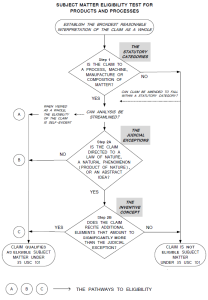

2019 PEG clarifies and revises the procedures for determining whether a patent claim or patent application claim is directed to an abstract idea under Step 2A of the USPTO’s subject matter eligibility guidance in two ways. Step 2A now includes a Prong One and a Prong Two, discussed below. Based on our personal experience, the 2019 PEG has reduced the number of subject matter eligibility rejections, particularly with respect to abstract ideas.

Under Prong One of Step 2A, a patent examiner should determine whether the claim recites an abstract idea including one of (a) mathematical concepts, (b) certain methods of organizing human activity, and (c) mental processes. If the claim does not recite matter in one of these groupings of abstract ideas, it recites patentable subject matter except in very limited circumstances.

Previously, under Step 2A, an examiner would compare the claim with one or more Federal Circuit decisions identifying an abstract idea and the Examiner would explain why it was believed that the claim was similar to claims from the decisions. This led to unpredictable outcomes because many examiners applied the decisions in different ways.

Under Prong Two of Step 2A, if the claim does recite an abstract idea, an examiner should evaluate whether the claim as a whole integrates the recited judicial exception into a practical application of that exception. Prong Two is a new part of the analysis and represents a major change. It will likely take some time for Examiners to adjust to this new part of the analysis, but Prong Two may possibly lead to fewer patent eligibility rejections.

Step 2B of the analysis remains the same as in previous guidance. Under Step 2B, if the claim is directed to a judicial exception, and the claim as a whole does not integrate the recited judicial exception into a practical application of that exception, then the examiner should evaluate whether the claim provides an inventive concept. In short, the examiner is to determine whether the claim includes significantly more than the exception itself. If the examiner determines that the claim does include significantly more, then the claim is eligible.

If you would like to discuss patentable subject matter and how it relates to software, please reach out to John Bednarz.